How much should I charge? How much can I charge?

These are the classic questions made by anyone launching a new product or service. Sometimes we have strong guidelines in place like competitive product pricing to help make decisions. Other times, especially in completely new industries and sectors, pricing can feel like a Wild West of options.

Thankfully, assessing the optimum price for a product or service doesn’t have to be as arbitrary as throwing spaghetti against a wall and seeing what sticks. There are a variety of objective, data-based approaches that not only let you explore optimum price but also the interplay between price and product benefits. Leveraging any of these approaches takes the guessing game out of pricing and lets you set a number that you can feel confident will work for your business and your customers.

Pricing Strategy 101 – To be Visa or American Express?

There are two key ways to think about your pricing strategy…

-

Revenue Maximization: This strategy says that your goal is to extract as much revenue as possible from each and every customer or transaction. Implicit in this strategy is that you’ll be setting your price points high enough that they will alienate a group of prospective buyers…but that you accept this outcome so that you can earn more revenue from those that do ultimately buy. We call this the American Express pricing approach.

-

Market Share Maximization: This strategy says that your goal is to “win” the greatest number of potential buyers as possible. Under this approach, you’ll likely price your products or services on the low end because you want as many customers as possible. In this scenario, you want to do anything to not alienate potential buyers. Companies like Visa and Mastercard fall under this category.

Remember, pricing strategy should be a reflection of your broader brand strategy, meaning that your product price should be greatly influenced by how you are positioning your brand and products in the broader market. We generally see two trends. Higher end luxury brands or product/service companies with few competitors and a small but ripe market can take advantage of the revenue maximization approach. In contrast, more mainstream brands or product/service companies targeting fairly large existing markets will often skew toward market share maximization.

That said, pricing strategy is merely a guide for helping your choose a general price direction. It does not lead to the actual pricing itself.

Let’s look at some research approaches to help arrive at the actual price.

Quantitative Approaches to Optimizing Price

We’ll start off by acknowledging that of course your price points need to ensure that your business is profitable. As a result, we’ll spare you conversations about cost-based pricing. But once you know the basic level you have to charge, the question remains: how much can you really charge? Rather than going with your gut, you can instead do a little research to land on the right answer.

Van Westendorp Price Sensitivity Meter

The Van Westendorp Price Sensitivity Meter (named after the guy that came up with it), uses a series of four questions given to respondents after they see a description of a product or service. These four questions are:

-

At what price would you consider the product/service to be of questionable quality?

-

At what price would you consider the product or service to be a bargain or a great deal?

-

At what price would you consider the product or service to seem expensive?

-

At what price would you consider the the product or service to be too expensive?

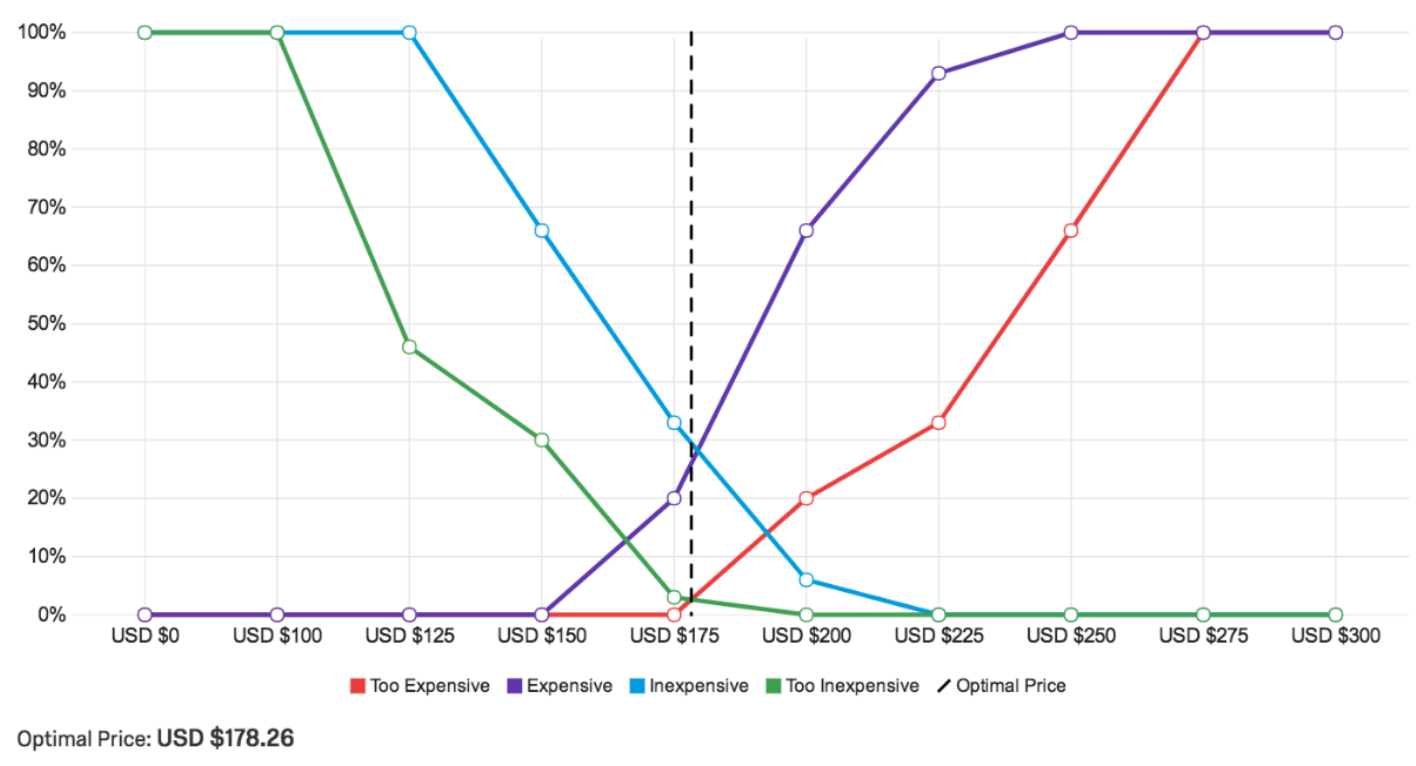

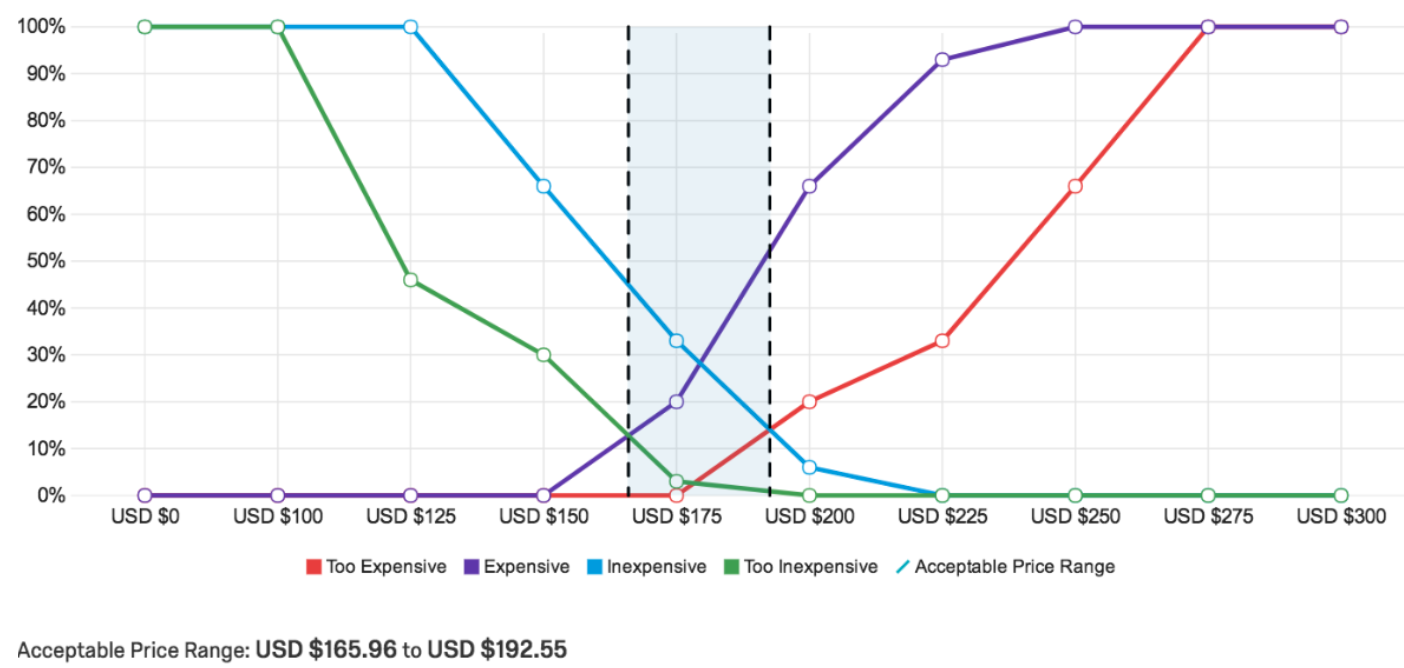

The end result is a series of line graphs that chart the distribution of how respondents answered each question. For instance, looking at the graph below, 20% of respondents said $200 was too expensive. But, 65% of respondents say it’s too expensive when priced at $250.

The Van Westendorp model selects the optimum price point where the “too expensive” and “too inexpensive” lines intersect.

The model also offers an acceptable price range, defined on the lower bound as the intersection of the “too inexpensive” and “expensive” lines and on the upper bound as the intersection of the “too expensive” and “inexpensive.” This range is key if you’re trying to work around certain margins or competitor pricing.

Pros: Van Westendorp’s main benefits come from its simplicity. Respondents only need to answer four questions and then they are done. Once the raw data is collected, it’s fairly simple to synthesize in a spreadsheet and map the optimum price and the ideal price range. Sharing and interpreting the results is similarly straightforward.

Cons: Unfortunately, it’s very simplicity is also it’s key disadvantage. The Van Westendorp model relies just on price as the determining purchase factor. Respondents aren’t given much information on the product features, nor are they given a chance to assess the product in a competitive environment. In essence, it asks about price in a vacuum, something no consumer every really does.

Our Assessment: It’s a nice and easy approach that offers actionable information. If you need a down and dirty way to price your products, this is the one. However, if you really want to gauge nuance and true price sensitivity, this option barely skims the surface.

Choice Based Conjoint Analysis

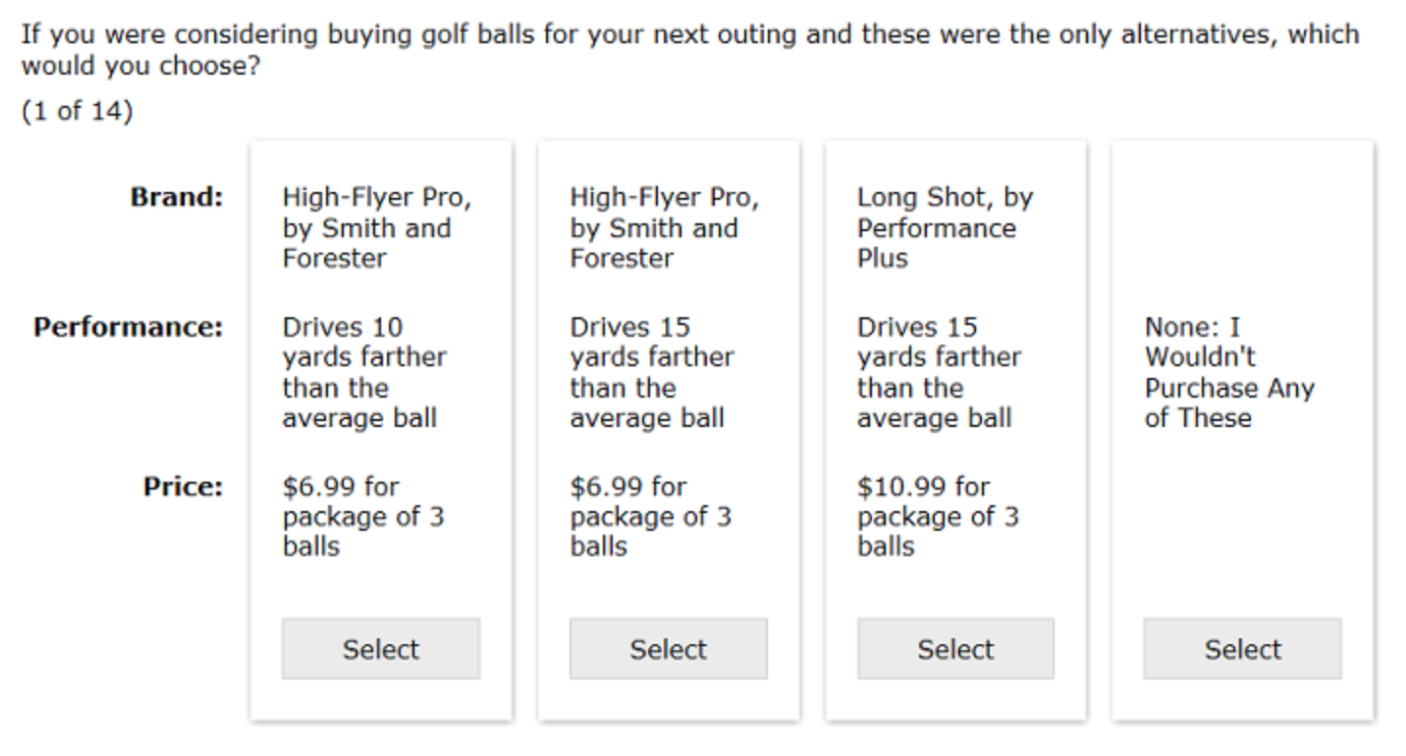

Choice-based conjoint (CBC) aims to more closely replicate the purchase-making process. Respondents are shown a screen with discrete product choices or bundles and are asked to select their preferred option. They are also given a chance to say if they would select none of the options. Once respondents select an option, the screen refreshes with a new batch of options. By putting your product at different price points up against other products at their current price points, you can gauge price sensitivity and the ideal product price.

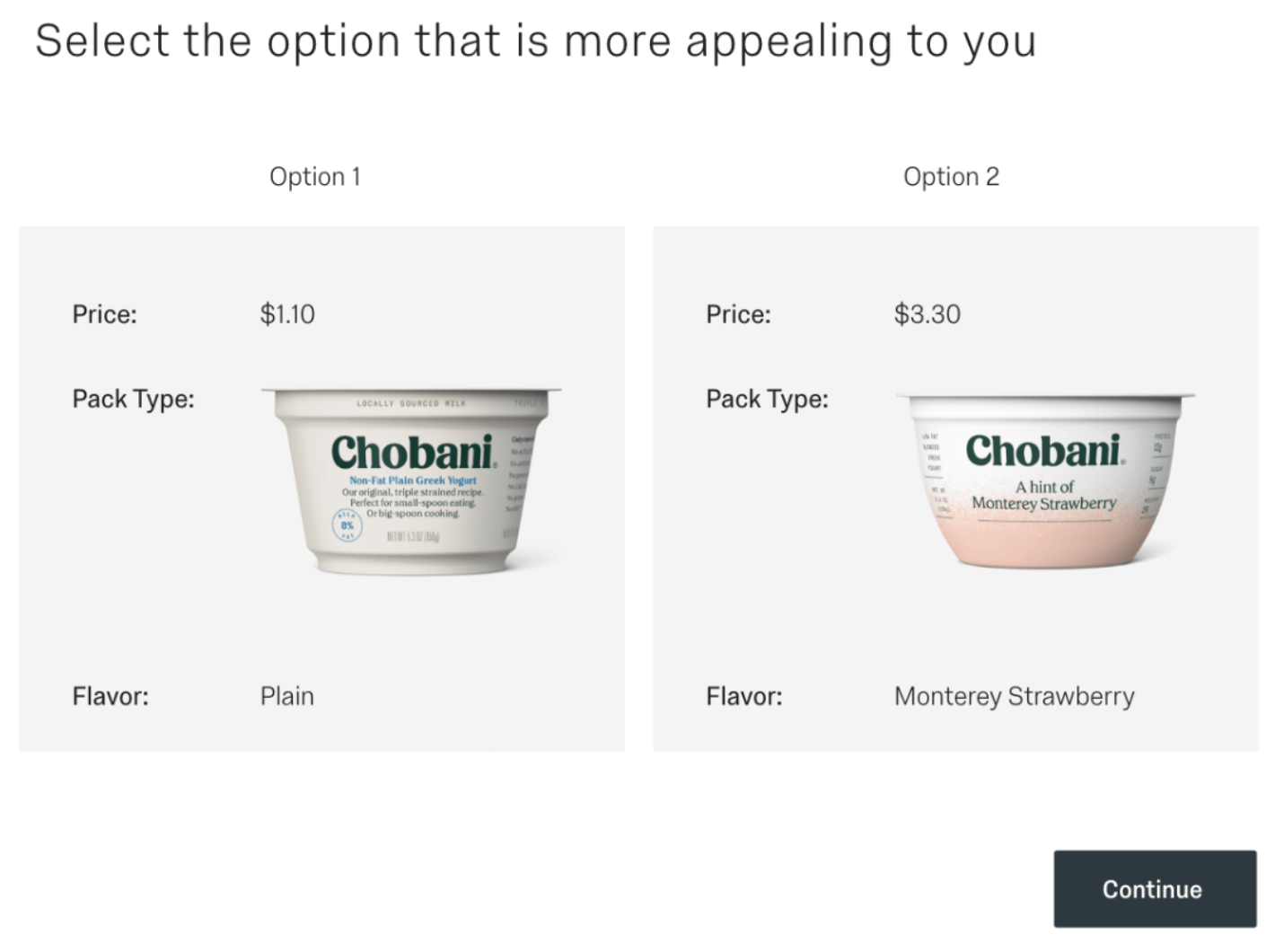

The experience looks similar to the screen below:

In consumer product testing, you can even replicate the on-shelf shopping experience. In this case, respondents are shown more realistic images like what you see below and click on their preferred product.

Pros: The biggest advantage of this approach is that it begins to approximate how consumers are forced to make purchase decisions. That is, the study replicates the natural process of making a lot small trade-offs at the same time while ensuring that you can include price as a revolving variable. As a result, it’s generally thought that CBC may yield more accurate responses. Additionally, by putting your product head-to-head with competitors, it lets you make a strong assessment for how your product at different prices really stands up in the market.

Cons: There are several downsides to this approach. To begin with, respondents only select their favorite choice, but they have no way of indicating if they have a strong or weak preference for that option. Further, because the variables themselves stay constant, it’s impossible to understand how valuable unique variables (e.g. Size) or variable values (e.g. 8 oz, 10 oz) are at driving a respondent’s preference. When it comes to pricing, we can’t gauge if the presence or absence of certain product feature is impacting price sensitivity. And, last but not least, by only showing the same product options (i.e. each bundle is always made up of the same variables with the same values), the experience can feel redundant to respondents.

Our Assessment: CBC is a solid compromise option between the Van Westendorp model above and the third option we’ll introduce below. The addition of a more real-world comparison approach creates more confidence in the ultimate findings. Further, it requires less time of respondents which is ideal when looking for a lighter-weight solution. It’s not the best-in-class option…but it requires less time and cost to execute. And, frankly, in robust product categories where very few variables change, the static nature of this model is just right.

Adaptive Choice Based Conjoint Analysis

Adaptive choice-based conjoint (ACBC) takes the CBC approach we just detailed to the next level by responding to the inherent weaknesses in the CBC approach: the repetitive, same-looking choices that may not be what a respondent actually wants.

Here’s how it works. Just like in the CBC approach, respondents will be shown different configurations of your product and will be asked to select their preferred option. Each bundle will have the same features (e.g. Price, Flavor, Size) but the actual value of those features changes. For instance, in the example below, both bundles have a price point and flavor, but the actual price and flavors are different. Respondents select their preferred option and then the screen refreshes to show new bundles with new variable values. With each selection, the system learns more and more about the respondent’s preferences and arrives at bundles that align better-and-better with their ideal blend of features.

Pros: ACBC comes with a lot of benefits. For starters, because the bundles adapt real-time based on respondent preferences, you’re able to measure the relative importance of difference features including price. Essentially, not only do you get to measure price sensitivity and the optimum price point but you can do so in the presence of other variables respondents are also taking into account. From the respondent perspective, ACBC is generally more engaging. Because the choices change each and every time, respondents don’t get board by seeing very similar scenarios time and time again.

Cons: As is typically the case, the more robust the research methodology, the longer the research time and the larger the sample size. Said another way, ACBC will cost more because it requires more expensive inputs.

Our Assessment: This is the premium solution and yields unbelievable intelligence not just around price but also the relative value of other product benefits you may be considering. That said, it can sometimes be the equivalent of driving a Ferrari when what you really need is a Camry. We generally recommend this solution when questions exist not just about price but also about the other features and benefits that make up a given product. This is often the superior choice in newly emerging markets or product categories where there are still a lot of unknowns.